[Author's Note:] The following [post, essay, whatever you care to call it] was originally published on March 12, 2003, when the current version of the Creative Commons licenses was Version 1. The author has not reviewed or revised the text to determine whether it accurately describes the workings of the current revisions of the Creative Commons licenses.

[Editor's Note:] This article assumes U.S. law.

Late last year, the Creative Commons project announced that it had prepared several form content licenses designed to allow people who publish on the internet and in other media to publicly license their work. The Creative Commons organization aims to increase the amount of creativity that the public can share and draw upon in further creation. "Taking inspiration in part from the Free Software Foundation's GNU General Public License (GNU GPL), Creative Commons has developed a Web application that helps people dedicate their creative works to the public domain -- or retain their copyright while licensing them as free for certain uses, on certain conditions." [link] Nearly four months later, the experiment is still only just beginning both for the Creative Commons organization and for the artists who license their work under Creative Commons licenses.

The release of the Creative Commons licenses spurred online discussion about the scope and impact of the licenses. Several questions came up among weblog writers, and I wrote a [blog] entry trying to resolve some of those questions. This entry covers the same questions, but has been expanded in some places and simplified in others. This entry does not rehash the earlier debate on the Creative Commons licenses. You can find a longer description of how these questions came up in the first entry.

One question that arose had to do with just how much content on a site one licenses by posting the Creative Commons graphic and link to a Creative Commons license on the front page of a website or weblog. Might it matter where you put the license? (Short answer: Yes, it can.) Does the license offer apply to old content as well as new content? (Short answer: Probably, if you put the license on the main page of the website.) The first part of this entry discusses those issues.

Several people have also wondered whether one could stop offering content under a Creative Commons license and whether that would effectively stop new people from acquiring the license. Although one can stop offering the Creative Commons license to new people, people may be able to obtain the license rights from someone else who already has rights under the license. The decision to stop offering the license won't make it illegal for more people to share the work.

The rest of this entry analyzes these questions in detail. After that discussion, you will find a short discussion of a few other technical issues and some comments on the sorts of factors one might think about when making any kind of copyright licensing decision.

No general discussion can take the place of expert legal advice tailored to fit one's own circumstances and goals. I hope this article will help people consider what they want to happen as they release their creativity to the world and how the Creative Commons licenses might interact with their goals. However, nuances in state contracting law might affect the interpretation of different clauses in the license, no matter how much I hope that this discussion reflects the law of most states. No one should rely on this article as definitive legal advice in the place of competent legal advice from a lawyer in one's own jurisdiction. This is especially true because no court has yet tried to interpret a Creative Commons license, so that little guidance exists on how to handle some of the questions that might give rise to disputes. Consult an attorney if you have specific concerns, and do not rely on this discussion as legal advice.

Contents

I. Total-Site and Partial-Site Content Licensing: It Can Matter Where You Put The License

A. Basic Mechanics

B. Getting Into Details: The Text of the License Introduces an Ambiguity as to the Scope of the License

C. Resolving the Ambiguity by Looking at the Web Site Operator's Conduct

D. Avoiding Ambiguity Through Words and Gestures

II. Removing the License From a Webpage: Revoking the Offer to Website Visitors

III. The Propagation Clause: Once People Get Rights Under the License, They Can Pass Them On To Others

IV. Other Legal and Technical Considerations

A. You Can Only License Your Own Copyrightable Works or Works That Others Have Given You Permission to License.

B. On Licensing in Metadata

V. Factors That Play Into Licensing Decisions

A. Enabling the Rapid Circulation of Expression

B. Retaining Control over Propagation and Association

C. Academic or Other Community Ethos

D. Publishing Through a Commercial Publisher

- In Conclusion

I. Total-Site and Partial-Site Content Licensing: It Can Matter Where You Put The License

The Creative Commons website invites copyright holders to offer their web sites or other creations under Creative Commons licenses by displaying the Creative Commons trademark along with a hyperlink to the specific license the author1 has chosen. Numerous web site operators have done this, but some have then shown confusion about just what that means. At least one web site operator incorrectly suggested that applying the license to the front page of a weblog only gave people permission to copy new entries added later than the Creative Commons graphic and link. If an author does not expressly limit what works the license applies to, a graphic and link to a Creative Commons license that appears on the main page of a website will probably operate to offer the license for all of the original, copyrightable content on the website for which the operator has rights.

A. Overview - License Timing and Interpretation

We can best describe the act of posting a link to a license on a webpage as offering rights to visitors. No one gets rights from the author at just that moment. The license does not give rights to everyone in the world automatically. Someone has to accept the offer in order to obtain the rights. In my view, when a visitor comes to the website, the license tells the visitor, "You, my visitors, may accept this offer by using the content you find here in these ways. As long as you use the content only in these ways, and you follow the other rules of this license, you have my permission to make use of this material that otherwise would infringe on my copyright monopoly. If you break the rules, though, you lose that permission automatically, and you can't rely on this license again afterward unless I specifically say so."

I've chosen using the rights of the license as the moment of acceptance, the moment where the licensee acquires the license rights, because I think it's the most tangible moment that says that the person copying the content intends to take advantage of the license rights. A court might disagree, but I think that acting under the terms of the license is the best way to indicate acceptance and should count as the time the license permission begins for that licensee. One could also build the Creative Commons license into a "click-wrap" license for a website; then that would be the best moment to say that the license agreement happened. Most of us probably think that'd be silly, but one could do that.

The rules of contract interpretation, which are generally part of state law, govern the interpretation of licenses. Not all licenses are contracts, but the same interpretive toolkit applies. The major rules of interpretation are pretty consistent throughout the United States, but states can vary in some of the details, and details might make a difference. We begin interpreting any license by looking at the words first. Courts try to give the words their ordinary meaning, informed by the ordinary custom and usage of the words. That might include the custom in a business community, and terms of art (legal terms and 'magic words') in relevant law will count, too.

If a contract term has ambiguous language, courts then look to external factors, including the conduct of the parties to the agreement. The court will try to interpret the agreement to achieve its general intent. If it looks to the conduct of the parties to help interpret the license or to tell when the license agreement happened, it will try to decide what a reasonable observer would believe that the conduct meant in those circumstances. This is called an "objective" standard for interpreting the meaning of conduct. The court will not try to determine what the parties "really meant," at least not unless there is evidence that one party knew or should have known that the other party meant something different (and that depends on the state whose law applies to the agreement). So, if there is ambiguity in the license, we should resolve it according to the 'objective' reading of the parties' conduct, not what the licensor was subjectively thinking. Also, the courts generally construe ambiguities against the person who drew up the contract. In the Creative Commons licensing case, a third party came up with the contract text, but it's still up to the person presenting the license offer -- the copyright holder, in this case -- to know and to express clearly what he or she intends.

Imagine that a weblogger places the Creative Commons graphic on the front page of a weblog and does nothing else differently, but later insists that the license applies only to entries added after he added the license. Another author says that the license covers what's on the front page of the weblog, but not entries that appear only in the archives. Is either right? I would argue 'no.' The license applies to everything in the website for which the author holds the copyright. Let's analyze why.

B. The Text of the License Introduces an Ambiguity as to the Scope of the License

The text of the license does not clearly state what work the copyright holder intends to license with it, so we have to look outside the text to resolve the question of "how much." There's a good reason the text doesn't expressly say what work it covers; the form license has to function for all kinds of different works. It says only, "'Work' means the copyrightable work of authorship offered under the terms of this License." So, we have to interpret what that means. A copyright holder can license old works as well as new ones, so there's no law that automatically excludes prior entries from the license just because of when those entries appeared.

The meaning of "work of authorship" under copyright law doesn't tell us how much of the website falls under the license. It only tells us that the license could mean both the individual entries and the compilation of them in the form of a weblog, because both are copyrightable "works." Copyright law thus allows there to be works within other works. The Copyright Act of 1976 doesn't define "work" in the definitions section. See 17 U.S.C. § 101. Sections 102 and 103 describe the basics of what copyright law covers enough to help us get an idea of what "work" means, but don't in the end say anything about the scope of the license. The 'Work' in the license could refer to an entry or set of entries, but it could also include the entire website "compilation," including both the entries and the overall arrangement. The use of the term "work of authorship" doesn't tell us what works of authorship on the website count for the license. It could refer to the whole website, but the ambiguity remains.

C. Resolving the Ambiguity by Looking at the Web Site Operator's Conduct

The rest of that license clause says that the license covers the work "offered under the terms of this license." Since the license doesn't tell us in words just what work that offer includes, we look at the context of the offer. We look at the online words and gestures of the parties, especially the website operator who makes the offer. We look at them applying that "objective" standard, asking how a reasonable observer would interpret the parties' behavior in those circumstances.

If an author or other copyright holder puts a Creative Commons license on the front page of a website and does not expressly say that the license doesn't apply to the entire site, then it's most reasonable to interpret that license to cover the entire website. (That is, to the author's own copyrightable creativity on that website.) A visitor has no means to discover what content came before the license offer and what came after, nor does the visitor have any reason to suspect that the author intends to offer the license only for some of the content on the site. If a license appeared among the title pages of a book of essays, that would lead the reader reasonably to believe that the license applied to the entire book, not just the title pages, and not just the first essay. A 'shrinkwrap' license that arrives with software can be most reasonably interpreted to apply to all the software, unless some of the programs have different 'clickwrap' licenses.

Considering the alternatives open to the website operator helps confirm this idea. It would be a different story if the author selectively applied the Creative Commons license or other licenses to individual weblog entries, and indicated no license or a different license on the site's main page. Or, the author could put a Creative Commons license on the main page, but indicate that a particular entry or page does not fall under the license. In that scenario, visitors would have no reason to believe that all of the content of the weblog fell under the license. Where the author simply displays the link to the Creative Commons license on the main page and does nothing else, the most reasonable interpretation is that the author has chosen to offer the entire contents of the site under the Creative Commons license.

D. Avoiding Ambiguity Through Words and Gestures

As you've figured out by now, it should be possible to take control of this ambiguity and to resolve it clearly through words and online gestures. For example, one might include prominent text by the license graphic and link indicating any limitations to the content one offers under the license. A website operator could also indicate no license (or something like "All Rights Reserved Except As Otherwise Indicated") on the main page or template for the site, and could then license each entry or webpage separately.

The "integration" or "merger" clause in the license should not prevent a court from looking outside the text of the license to determine what work the copyright holder offers under the license. The merger clause says, "This License constitutes the entire agreement between the parties with respect to the Work licensed here. There are no understandings, agreements or representations with respect to the Work not specified here." This language aims to keep other possible licensing terms out of the agreement. However, there's still an ambiguity about what counts as the work offered under the terms of the license, and when that kind of ambiguity exists, the court can look outside of the license to resolve the ambiguity even when the license has a merger clause like this one. However, it'd be a very good idea to make sure that the web site states the limitation in a prominent and sensible place, like right by the license graphic on any page where it might appear.

One should not try to change the substance of the license agreement (for example, by saying that one of the clauses in the license doesn't apply at all) with writing near the license graphic. First, the merger clause might effectively exclude it. Moreover, that would violate the rules according to which Creative Commons allows people to use its trademark "(CC) Some Rights Reserved" graphic. Web site operators should not try to modify the terms of the license with language outside the license text. Someone who dislikes the terms of the license should not try to use it.

II. Removing the License From a Webpage: Revoking the Offer to Website Visitors

A Creative Commons license tells visitors to a website that they may copy material from the site, and that as long as they play by the rules in the license, the author cannot take away that permission. This is what the license means by saying it is "irrevocable." The "irrevocability" of the license that each visitor gets does not mean that the author must forevermore offer the license to all visitors. It only means that visitors who have already accepted that offer cannot lose permission unless they break the rules.

On the other hand, if an author chooses to dedicate his or her work to the public domain, the author has then made a change to the underlying copyright protection for the work. In that case, the author has relinquished all copyright protection. Once the author has dedicated the work to the public domain, nobody needs a license, not even a Creative Commons license, to copy the work or to use it in any other way.

Unless the author chooses the Creative Commons public domain dedication, displaying the Creative Commons license leaves copyright protection in place, but offers the terms of the license to visitors. This means that as a technical matter, only visitors who come to the website may receive those licensing terms from the author. Professor Lawrence Lessig described the irrevocability term this way:

... [J]ust because you can't revoke a particular license doesn't mean you can't revoke the offer. If, for example, you offer content under a CC license for a month, and then change your mind, you can stop offering the content under that license. Anyone who accepted your offer while it was valid, of course, has a deal. But no one after you withdraw the offer can accept anymore. [link]

If I build a website and place the Creative Commons license on the website, have one visitor who copies material, and take the license off the next day, then only that one visitor obtained the rights in the license. As the next section explains, however, this is not the end of the story. Even if the author stops offering a Creative Commons license, there will still be a way for new people to get the rights of the Creative Commons license, because people who get rights through a Creative Commons license pass them on each time they give a copy of the work to someone new.

III. The Propagation Clause: Once People Get Rights Under the License, They Can Pass Them On To Others (even if you wish they wouldn't)

Paragraph 8 of every Creative Commons license includes the following text:

Each time You distribute or publicly digitally perform the Work or a Collective Work, the Licensor offers to the recipient a license to the Work on the same terms and conditions as the license granted to You under this License.

I call this clause the "propagation clause" because it is designed to enable the spread of both (1) the content and (2) the license's grant of permission to share the content. Ideally, if everyone plays by the rules in the license, then everyone gets to share the work.

C.C. License and Work Propagation

A Hypothetical Scenario of Rights in Creative Commons Licensing

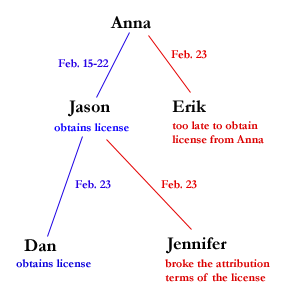

Imagine the following scenario. Anna Logue has a weblog. She'd been writing for a while and already had several entries when on February 15th, she added a Creative Commons license that displayed the Creative Commons graphic and a link to the "Attribution-NoDerivs-NonCommercial" license on her weblog's homepage. She adds more entries. During this time, she gets 350 visitors to her site. One of them, Jason, copies one of Anna's posts in its entirety, properly attributes the text to Anna, and posts it on a noncommercial weblog. Anna gets cold feet, and at 5:15 p.m. on the 22nd, she removes the Creative Commons graphic and all links to the Creative Commons license. On the 23rd, Erik copies the entirety of the same post Jason copied from Anna's weblog into his own noncommercial weblog, with proper attribution. Also on the 23rd, Dan copies the entry from Jason's weblog into his own noncommercial weblog. Jennifer copies the entry from Jason's weblog, but in her copy, she doesn't indicate who first wrote the entry.

What happened when Anna took the Creative Commons license graphic and link off of her webpage? We have a few possibilities:

(1) When the author removes the Creative Commons license, anyone who relied

on it to copy content from the site may continue to copy that content under the

license, but no one new may copy the content.

(2) When the author removes the

Creative Commons license, everyone may nonetheless continue to rely on the

Creative Commons license and to copy the work.

(3) When the author removes

the Creative Commons license, no one arriving at the author's site may copy the

material, but someone who obtains a copy from someone else who received

the work under the Creative Commons license may make copies and distribute

it.

(4) The license terminates and no one at all may copy the work

anymore.

The fourth option is plainly wrong, because the license says so. The license reads,

Subject to the above terms and conditions, the license granted here is perpetual (for the duration of the applicable copyright in the Work). . . .

People who have copied the work under the license thus retain the rights that the license gives them when Anna stops offering it to new visitors. Anna also cannot revoke licenses by writing a revocation, because she gave up that power in the license.

The second description fails to account for the limitation that only people who can get the rights under the Creative Commons license can copy the material. If someone new comes to Anna's website after she removes the license offer, that person can't copy from Anna without permission. Erik did not have permission to copy from Anna's website, so his copy infringes Anna's copyright. That makes it seem like the first description above is accurate, but there's still a catch.

The propagation clause passes on the rights to the work with every distribution or public digital performance of the work. If someone copied one of Anna's weblog entries while the license was on Anna's site and then followed all of the rules in the Creative Commons license, the propagation clause will offer the Creative Commons license to everyone who gets a copy from that person. This means that Dan legitimately copied from Jason and also now has all of the Creative Commons license rights. Jennifer could have gotten those rights, too, but she broke the terms of the Creative Commons attribution license by failing to attribute the post properly. Even if Jennifer had the license rights for a while, they now terminate, and she infringes Anna's copyright by using the work.

Copying Anna's Work: Who has a legitimate copy and license?

Because Jennifer broke the rules of the license, the license permanently excludes her from accepting the Creative Commons license from anyone unless Anna approves. That's the result of adding paragraph 7.a of the licenses to paragraph 1.f, which says that the "You" to whom the License is offered must be someone "who has not previously violated the terms of this License with respect to the Work, or who has received express permission from the Licensor to exercise rights under this License despite a previous violation."

The propagation clause puts the "commons" in the Creative Commons licenses, so it's very important to the licensing system. It enables anyone who plays by the license rules to share the work and pass their rights on to others. It's difficult to discern exactly how the propagation clause works in terms of legal doctrine. Normally, when a license gives someone else the right to pass the license on to other people, that's called the privilege to sublicense the work. However, the Creative Commons license explicitly forbids people who get rights under the license from sublicensing the work to others. Perhaps the authors of the Creative Commons licenses included that provision to make it clear that people getting rights from the license do not have any power to change the licensing rules for other people. Instead, the licenses purport to offer an identical license to anyone to whom the licensee gives a copy of the work. Under ordinary contract law, one can revoke an offer that hasn't been accepted yet, even a written offer, unless someone paid for the offer to be unrevocable. I'm not sure anything in the license makes that impossible, even though that's the goal of the license.

Although this leaves unresolved questions about the details of how the propagation clause works, authors should assume that the clause does what it says it does. Copyright holders definitely should not hold out their works under a Creative Commons license while intending to challenge the enforceability of the propagation clause later on. (First, that's duplicitous; second, courts don't like to invalidate terms in a way that would favor the person who chose those terms in the first place.) Authors who do not intend to put their works into a lasting network of sharing should consider alternatives to the Creative Commons licenses.

IV. Other Legal and Technical Considerations

A. You Can Only License Your Own Copyrightable Works or Works That Others Have Given You Permission to License.

One may not license someone else's work without permission to license it. In order to grant a license, one needs either (1) the exclusive right to do the sort of actities one is licensing others to do or (2) a license from the copyright holder to sublicense the work. If a website operator puts a Creative Commons license on a web site, that license will not cover material in which the operator does not hold the copyright. It will only cover the operator's own original copyrightable work. If you do use a Creative Commons license to cover your entire site, you should consider indicating whenever you offer for download or display a document that the license doesn't cover, to avoid the risk of confusing people about their rights.

Someone who uses a Creative Commons license and also copies someone else's work under a Creative Commons license should link to the license the author selected when displaying or distributing the author's work. The author and the copier might have chosen different Creative Commons licenses, and the license denies the copier permission to change the rules that the author chose for distribution of his or her work. In short, you can't apply your Creative Commons license to someone else's work.

The Creative Commons license asks you always to display and/or link to the Creative Commons license of the author's choice when you display or copy a work, so one should probably post the Creative Commons graphic and link on the individual work even if one has the very same license to cover the entire website.

A website might have more copyrightable content than just text and photographs. Images, customized display templates or markup, and other content might fall under copyright as well, and a general license for the website would apply to those aspects of the website as well.

B. On Licensing in Metadata

"Metadata" means "data about data," and in this context refers to ways to describe or summarize the data that exists, for example, on a website. Some people have begun to modify popular XML schemas2 for metadata to allow the XML-based summary of a weblog's content to indicate whether the content may be copied under the terms of a Creative Commons license. This has prompted the question, "Just what does the XML Creative Commons tag mean?" Does that tag purport to offer a license in (1) the XML content only, or (2) the entire HTML content of the weblog? If it's the latter, does the schema provide for users to license individual posts only, or must they commit to licensing entire weblogs?

Unfortunately, there's not even a halfway solid answer to those questions. There are good arguments that we should narrowly interpret an XML-tag Creative Commons license to apply only to the XML-rendered content, especially if the weblog does not contain a Creative Commons license offer or grants the Creative Commons license in more narrow circumstances. An XML summary of a website is at least partly a derivative work based on that website. It's not necessarily safe to assume that the original comes under the same license as the derivative work. As far as I am aware, XML also offers few ways for authors to explain how much of the site the Creative Commons license covers. Because of these limitations, we should interpret the XML tag in a limited way. One counterargument is that the XML summary of a website is about the website, so that an XML license tag included there should also be interpreted as an offer about the website. At present, however, embedding a link to a license in an XML summary is a very unorthodox method for making a legally operative offer to others, and we should consider the risk that authors might be unable to clearly express in that medium what they're trying to do.

We might interpret the XML tag license only to indicate that some of the content on the website is available under the license. On that view, users should not automatically assume that all of the content is available under the license. That interpretation would make the XML tag more like a statement that one can find Creative Commons licensed content on the website, so that the tag would not be enough to operate as an offer on its own.

This interpretation question is so difficult because ordinary custom, usage, and conduct offer much less guidance than they do with a web page. We have enough practical experience with web sites that we can make sense of what it means to include license terms on a website. We don't have nearly as good an idea what it means to include a link to a license in metadata about a webpage and to have something different or nothing at all about licensing on the webpage itself.

If XML data about licensing can be made "rich" enough to describe clearly the different sorts of limitations that an author could legitimately put on the scope of a license, it might then make more sense to say that the XML license tag is an offer that applies to the site as well as the summary. However, I'm not comfortable with that interpretation until the expressive possibilities of the metadata adequately cover the author's alternatives.

Unfortunately, I can't even provide a halfway safe assessment as to what a Creative Commons license link in an XML site summary means legally. Authors who choose to license anything short of the entire website might want to avoid using XML licensing tags until the community can develop more consensus on what it means to put something like this in XML.

V. Factors That Play Into Licensing Decisions

[This section is almost identical to an earlier entry.]

People make copyright licensing decisions in different ways for different reasons. Only the author can make the final assessment of whom to give permission to copy, display, or perform the author's work and for what reasons. I can only talk in broad terms about some of the reasons people might or might not choose to license works under a Creative Commons license. However, I don't want readers to get the impression that I'm saying that certain categories of people with certain interests should choose a certain license. All I want to do here is to talk about some of the factors authors might think about, in order to spur the imaginations of readers. If you use this for anything at all, use it as a starting place and not an ending place for your thoughts about licensing.

Let's start by remembering the starting position of licensing: people may not make copies of copyrighted material without permission from the person who holds the copyright. When you publish material on the web, you offer an "implied license" for me to download a copy and display it on my computer screen -- why else would you put it on the internet? -- but you don't give me permission to do anything else with it. Now, why might you give people broader permission to copy and use your work? Why might you not?

A. Enabling the Rapid Circulation of Expression

Although fair use allows people to copy parts of what you say for the purposes of comment and criticism, you might want to make it clear to readers that you want them to copy all of what you say if they want to. It might mean much more for you to see your creativity passed around from person to person than it would mean to hold out in hopes of obtaining money from a commercial publisher for a more limited, controlled release. The Creative Commons licenses are designed to allow an author to offer his or her works for people to pass around as much as they like, as long as they follow certain rules.

For example, suppose that I have an essay that I'm happy to have people passing around. I may want to see my work circulating. I only want to make sure that they identify me as the author, that they don't try to add to it or make their own changes to it, and that they don't make money off of the process (because in the unlikely case someone is going to make money off of this work, I want in on the deal). I may well find that the "Attribution-NoDerivs-Noncommercial" Creative Commons license fits very well with my goals. If I have different goals or fewer concerns, a different Creative Commons license may better fulfill my goals. For example, if I want people to take my work and add their own creativity to it or put it to new uses, I may want a license that allows derivative uses.

B. Retaining Control over Propagation and Association

Suppose, however, that I want to be able to say, "I only want people to get this work from my own website, and I want to have the legal power to halt further copying if I decide to release a newer edition or retract the essay. First, let's keep in mind that fair use doctrine will still allow people to quote content from my essay, even if I can stop all further licensing of the work. But still, suppose I want to retain whatever control over distribution the law will give me. In that case, the Creative Commons licenses' propagation clause will frustrate my goals. For example, one substantial reason this article is not licensed under a Creative Commons license is that I'm still working on it -- and I may always be. I want to know and control where copies go so that when I rethink something and make major changes, there's less out of date or incorrect material floating around.

I may also want to limit who may use my work and for what purposes. Fpr example, if I am a photographer, I may be very pleased to find my photo displayed on a charitable organization's website, and much less pleased to find it displayed on the website of a racist organization. If I have licensed my photo to all comers for all non-profit purposes, both of these organizations may copy and display it. Only if I have retained the power to grant licenses to people on an individual basis will I be able to choose the charitable organization and exclude the racist one. Is this likely to happen to most people who release their work online? Probably not, but it's still something to consider.

Meanwhile, remember that even restrictive licensing will not prevent people from copying some of the material to the extent that it helps them comment on or criticize the work. Comment and criticism lie close to the heart of fair use. They won't justify unlimited copying, though. Fair use doctrine includes the idea that people may not copy more than they need in order to make their critical points, but within those vague limits they will still be able to copy. Restrictive licensing will not allow anyone to "lock down" work against criticism. If someone publishes a scathing weblog entry that turns out to be a frightfully bad idea, fair use will almost certainly let me quote some of that content in the context of commenting on it, even if the author decides to retract and delete the entry.

C. Academic or Other Community Ethos

Some writers have chosen to apply the Creative Commons licenses to their webpages and/or weblogs because they believe that it best reflects the prevailing intellectual ethic in their academic community. A Creative Commons license makes it easier for others to copy interesting work and share it with others in the community. When the community places a high value on the sharing of ideas and expression, the Creative Commons license represents a positive gift to the community. Of course, it doesn't hurt in terms of reputational reward, either; the author may take advantage of easy word-of-mouth distribution while the community notices and appreciates it. Fair use doctrine facilitates some scholarly copying, but a Creative Commons license bypasses the question of fair use for most purposes.

D. Publishing Through a Commercial Publisher

Commercial publishers, including the publishers of most academic journals, want to be the first to publish the material they print. In academic publishing circles, a lot of prestige can come from being first. Academic publishers also tend to demand the author's entire copyright, though they may license rights for certain uses back to the author as part of the copyright transfer agreement. Many academic journals -- especially in the sciences -- have taken to charging astonishingly high prices for print and digital editions. Publishers will not be eager to compete with a free Creative Commons licensed edition of the same article that anyone can download from the author's webpage (or from the webpage of anyone else who holds the Creative Commons license in the work).

Cory Doctorow recently released his novel Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom online under a Creative Commons license as well as in book form through a commercial publisher. We'll never really be able to tell exactly how this decision has affected book sales revenues for Doctorow and his publisher. However, it's almost certain that he dramatically increased the circulation of the book, at least over the short term. The decision also brought him -- to use his own terminology -- substantial amounts of 'whuffie,' reputational reward. The idea of 'whuffie' and discussions about reputational economics probably would not be nearly as popular in online circles if there were no online, Creative Commons licensed edition of Down and Out.

The publisher's requirements issue may be less significant for people who are only contemplating using the Creative Commons license for more casual publications like weblogs. The question may come up only if the author posts drafts of professional articles (or draft chapters of fictional work, or poems that he or she intends to publish, etc.) to the weblog. The topic will certainly come up, though, if the author wants to release the very same material online for free and in print for charge.

If the free online scholarship movement catches on more fully in the next several years, the face of academic publishing may also become much more friendly to Creative Commons licensing. Meanwhile, authors who depend on commercial publishers for academic reputation building or financial income should keep in mind the rights that their publishers are likely to demand.

In Conclusion

Authors and other copyright holders who want to share their work, who want to see their work passed around and put to new uses, should consider using the Creative Commons licenses. However, they should be aware of the potential permanence of some aspects of the licensing decision. I hope that this essay helps people understand and contemplate these issues.

At the same time, I need to advise readers once more that this entry cannot substitute for qualified legal advice tailored to one's own circumstances. It would not be wise to take my views as a conclusive interpretation of the facts in any particular case, because real life cases present specific and diverse facts that my generalized discussion cannot reflect. I've tried to address only a few stereotypical and imaginary cases. The licenses also present possible unresolved legal questions. If you have legal questions about your licensing decisions or concerns about copying, you should consult with an attorney in your jurisdiction.

Notes:

1I use the term "author" the way the copyright law does -- to refer to anyone who creates copyrightable work, not just to people who write.

2I'm not terribly well-informed about XML, so I apologize if I inaccurately use this terminology. I'm trying to refer to customizations in versions of RSS/RDF.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.

Timothy Hadley is a lawyer who lives in Broomfield, Colorado. His blog is Math Class for Poets.