Custom Roll

Bombay. Mumbai. Janus faced, as good a starting point as any, especially so without a map and with “the guide” himself in the dark.

The polite thing would be to let him orientate himself awhile; allow for the light, and the population density, and the sound of this place to infuse his spirit, embolden him. For he does need fortifying – even the quickest of glances will confirm that. Hanging around half-known in someone else’s account has become something of a signature trait over the years. And it has weakened him, the shadow he originally “learned” in distant doorways – stairwells, to be precise – now a pall over what was once so bold.

Stick around for long enough near Lower Parel, or Dadar, and more often than not he’ll appear late afternoon, clearly unconvinced by the mission – “guiding” other firangis, the bolder ones who’ve ventured beyond the comforts of Colaba and its “gateway-to-experience” backpacker colony – but with the traipse of a man who is only there as he can’t think of anywhere better to be.

He bears the hallmark of the fugitive. It’s there in the eyes with their flatlined glaze, or in that slump under the kurta, yet there’s also something entitled marking him out from the other flatliners these streets specialise in. Their cards were dealt long ago, with an unpaid doctor’s bill, or an escalating dispute over livestock or land. Bloodlines, their primal course, smuggled in with the dust and intrigue, and given all of that, the city by the sea in some ways a step up for most of them.

His descent though has been deeper and somehow more unforgiveable.

Even the pocket-maar looks at him with a special kind of contempt. He is not from this country, which means he lives this way by choice. And that is something else he shares with very few. Yet another reason, he would say, to stay half-cloaked in shadow.

But it was true, he had arrived by plane with bona fide documents, and it wasn’t just the light, and the density, or the noise, which hung off him like a firangi stink. Another giveaway in how even the sweat would trace different contours on his back, stiffer nowadays but at one time gym-sprung. Not sinewy though in the local fashion, keened by years of shortage. His compadrés at street level were lithe, raw boned, all stretch and miracle in vest and dhoti, the weight of the city borne on deceptively narrow shoulders. Yet in his case there was still some evidence of the dumb-bells in the way he rolled his shoulders. Behind the garb, a gym rat. The kurta no real disguise. For all the decorative tics and filmi stubble, there was just something very foreign about that body. No use pretending he didn’t move to Lata Mangeshkar, or Asha Bhosle, as though he wasn’t really hearing Curtis Mayfield, or Sylvia Striplin, the custom roll born to a Vilayet elsewhere.

So the sense of discomfort he sometimes felt wasn’t really to do with the light or the clamour.

It had never just been about that.

If he was being honest, he’d tell you it went back to his early days on that estate, in that elsewhere, at school, learning, if not to “pass,” then at any rate to be invisible. Serving an apprenticeship. Though for what was anyone’s guess. Adolescence stumbling into adulthood, and now this other half-life. As if all he’d really done in the interim was to pack the unease into a suitcase and bring it with him, economy class.

Of course, today there’s every chance he’d be viewed as an “unreliable witness,” even to his own life, what with the disappearance of the estate and its rebirth as a “village.” Even he’d be hard pressed to believe such things as had once happened had done so on the same patch which now hosted executive parking bays and the full panoply of “gated” comforts. Yet on a certain kind of day, before the humidity took its toll on his navigational prowess and a particular way with the firangis that had originally earned him the local nickname, “the guide,” he might have said this. His reincarnated manor meant that he too had made the journey from a village to the city, and so he too was entitled to a tilt at its attractions.

Aap-ka naam? Mera naam muddled in with the stubble and a memory. Manna for the backpacking seekers, the bolder ones drawn here by the city’s other aspect: the frisson of its demimonde they’d first felt on the page. All those tales of gangsters and bar girls and a city on the make. By now the author names were familiar to him too. Thayil and Chandra, Mehta, and the other one, the Australian. Their books kept popping up in his eyeline, and the faces they obscured had almost certainly arrived, like him, from the skies with visas. So he knew the form. Honey for the bees, then when the firangis were good and close, some antique tremor, leaking asphalt into the throat.

‘How come my English is so good? Well, I’ll let you into a little secret. That’s ’cos originally I’m from England.’

Homespun laughs too, born of a shared lie of home. Though a lie was often all it took.

No one came here looking for the truth. That took place far away, in the village, the “real” India, under clouds of hemp and the protective supervision of fellow travellers. Everyone knew that, didn’t they? And then he’d briefly wonder whether he was thinking aloud, knowing full well that he was no madman. Nectar liberally sprinkled on the surprised vernacular if he sensed interest from one of the fresh foreign arrivals. That’s right, how’s it going? Or at especially playful moments, the rerouted JA option, ‘Wha’a’g’wan?’ which rarely failed to find its mark, backpacking eyes lighting up at the prospect of an unexpectedly familiar fetish. He knew the form, knew how for these middle class kids the Black British snippet was yet somehow more accessible than the thoroughly alien sounds of the local dialect. And at those moments there was nothing random about his manner when he saw the relief in backpacking eyes. He would size up the way the girls were drawn in, despite the advice of their guidebooks, or the advance warning of friends and family. Then he’d notice the boys who these girls were with, would see them, as if for the first time.

He’d see how novel an experience it was for these boys to actually have to bargain. But much to his displeasure, he’d also note how their fair skin meant they had the ideal currency to fall back on even when the parlaying broke down and the sweat and the confusion had their say. That longer history, of masters and servants, of expecting to be listened to, nearly always having the final word. And after a bit, he too would find himself plagued by the heat and the smell. This also troubled him, the shared afflictions somehow narrowing the gap between him and the other firangis.

He sensed that the other flatliners knew this too, alerted by lifetimes dedicated to examining the subtle shift, the point at which someone changed from “traveller” to “customer,” or in his case from “here” to that other place. And just like that, loosening a muttered trail of choothias which were fooling no one, he was back “there” again.

He recalled little snippets – ‘You’re going home in a London ambulance’ – and this far away it was almost funny. Back in the village before it was even that.

He remembered its dress codes.

Polyester/cotton, patterned, top button done up long before Pendletons and low-riders and the Mongolian mystique of those other desert born faces he’d later see in the films.

What stayed with him though wasn’t a style from the pictures, or from any mag.

Just hard up, immigrant instinct and some vague desire not to be a burden. He’d seen his Dad’s payslips. They’d never have stretched to boxfresh.

So instead he made do with: turmeric cords, jumble sale chic and, on a good day, plimsoles.

As far as he could tell, trainers were for the other kids who seemed untroubled mouthing off at their parents when they came to collect them after school. When the air turned bright blue, as it nearly always did at these moments, he’d look down, and usually the perp would be wearing trainers. Real ones too, not the cheap knockoffs that made it to the local market. It never made sense to him how so many of them also managed to get the free school lunches. Then again, in that place, a lot of things didn’t really add up.

Still, in the Mumbai heat all that was really left of that time now was a strange fish-eye lens, where the snippets, like frayed polaroids, fell somewhere between mustard and blank.

When he turned to look again at the fresh faced, healthy, gap year fugitives, already perspiring from the local heat, what he really saw belonged to the other end of a pipeline, a world away from here. In his mind’s eye a skittish young boy stranded in a south London foot tunnel, the pipeline streaming effluent into an afterthought.

He saw the tribes with their labelled warpaint. Shermans, sta-prest, Blakey’s, morphing into fresh Kappa, Pierre Cardin and Farah’s.

No expense spared by his foulmouthed classmates, but even so boxfresh (trainers) still couldn’t dispel the reek of the tanneries which surrounded them. South London, a holding pen for all the city’s disquiet. Scrambling the messages from one end of the pipeline to the other, so that one moment it was fine arts and the next “Fuck Art, Let’s Dance.” A ska soundtrack, though in reality the only sound he could remember was of the skinheads and their Blakey’s clicking all the way down the pipeline. Sectarian drip drip in the foot tunnel to the Isle of Dogs. By now he’d be sweating profusely too, and this is what would finally convince the backpackers that they were all on the same journey, subject to the same irritants. The point at which they’d make their first real error, the one he’d been waiting for. They’d decide to trust him.

That’s right, mate, we’re on the same journey. Trust me.

Trust, of course, the one commodity in perennially short supply, even in this city of commerce. And that was how he’d become their guide, with this city tilting a trickster cheek towards the Arabian Sea, but no more enchanted with him than the one he’d left behind.

His lip curled. It was all part of the transaction, the seekers with eyes of gilded wonderment, their guide with his own premeditated thoughts.

They passed the runners with tiffin carts, metal and wood, the axles greased with sweat, a human linseed oil. He nursed images of cricket bats swung at boneheads in the pushmepullyou dance of his youth. Sometimes they connected and the dance would thicken with a sickening crunch of bat on bone. Other times the bat met fresh air in an empty carousel, and the guide himself would be spinning from fist to boot to floor. The noise of the foot tunnel, of pursuit, or flight, gradually gave way to the sounds of car horns blaring, or the obliviousness of an ox-cart. The oleaginous film of the city’s chemistry licking every street corner. Sweat, paan, the putrefying remnants of street food. He would lead them deeper into the city’s convulsing guts. Ten minutes later the guide and his newly acquired followers would be in the foyer of The __________ Guest House, his commission assured. His perfunctory greeting to the proprietor could barely even be called that, now that both parties were wearily familiar with the routine. Backpacks remaining firmly on backs while Passports were gathered, and room rates, their negotiable “extras” ran the gauntlet of necessary haggle. Firangi noblesse oblige the one unwavering detail every time. And if his head still replayed those childhood memories, of hunters and the hunted, then the guide himself remained largely implacable, his linguistically familiar presence alone deemed sufficient by the backpackers as some kind of guarantee. We’re on the same journey. We trust him.

He tried not to roll his eyes when the inevitable bargaining started up. That older film roll of masters and servants, a compulsion evidently held on to well beyond Empire. For all his best efforts, a frown line made itself known. The transactional skim factored into the haggle was barely a drop in the ocean to these travellers, but the difference between eating well and having no choice for the locals. The guide, whilst belonging to neither eventuality, remained agitated, his guts keened by other hungers. Far away ones.

In the end they were all seekers really. These girls and boys in their search for “experience,” but for once in a place where they were the minority; and the guide, in an unexpected way also looking to them for validation, desperate to believe that the charade had heft, meaning, purpose. Never mind this place, he thought, these fools didn’t even know the first thing about the other place, where he, where they had all come from. It still gnawed away at him, an imbalance in the transaction. But then he reminded himself of how much easier his life was now and his thoughts grew less jagged. That was another life back when he’d first rolled the dice on custom. The memory was still sharp though.

A thin bead of sweat tickled the back of his neck. By the time it had weaved its way past shoulder blades he was back in the old place, full of nervous excitement.

There were witnesses and it was…

…Priceless.

The look on that herbert’s face when the guide tucked himself into a foetal ball and then just rolled down the freshly tarmaced ramp with the abandon only really available to the truly petrified. As if the fear had also frozen his logic.

All summer the asphalt had bubbled with a heat worthy of Dadar. But this was south London, and Dadar belonged to his future. So now, despite his best efforts, the shirt clinging to his skinny frame was still smudged with some loose flecks of tarmac, and that might take some explaining later. But for this instant, any amount of trouble was worth it just to appreciate the euphoria he felt on his triumphant ascent back to the summit, and the suicidal gauntlet thrown down before his chief tormentor of a little earlier.

‘Now you.’

Just hours before the whole class had made the sound of cracking whips when he’d walked in for the morning register.

It was all so predictable – ‘Roots’ had aired on consecutive nights as a “miniseries” over the Bank Holiday, and he might have known that little Bradley and Lisa, and Spenser and Debbie, would have been watching too. And they’d carried on making the whip noises right up until he challenged Paul Martin, their unofficial leader, to an after-school dare. The prize (and forfeit), of course, to be decided by the winner, but right now there was still the small matter of the conclusive roll.

Nobody moved, and for once nobody said anything either. Not Paul, nor his sidekick, Bradley. Not a peep, either, from the girls, though he noted a hint of impatience in the way Debbie stood there, hands firmly planted on hips. Taking that as his cue, the guide let the moment gestate, allowing another few seconds to pass, before repeating, this time with greater insistence.

‘Now you.’

It didn’t take long for the restlessness to spread, just as he had hoped it would. Bradley the first to break ranks.

‘Go on, Paul. Don’t let the Paki show you up.’

This seemed to embolden the others.

‘Yeah, go on, Paul. Go on, my son.’ (‘Son’!? The neck on these. All of eleven years old and already carrying on like they were grown ups.)

He thought he spied something unfamiliar in Paul’s eyes as they took in the tarmac ramp, perhaps playing around with the same permutations he had deliberately not allowed himself time to be scared by: of oncoming, but hidden, traffic approaching from around the blind corner; or a stray teacher wandering around and, at a push, even the Old Bill. (The previous week had seen a full-scale invasion of the neighbouring school and the estate had been crawling with uniforms ever since.) He could tell that Paul was overthinking it, and this notionally pleased him in its whirlwind embrace of road safety pleas and the green cross code. He considered the watermelon smash on those cautionary crash test dummy vids they were made to watch in class after that boy in the year above had been knocked down. And he knew that similar thoughts would be passing through Paul’s head as he prepared to meet the dare.

It was a side approach to the school, which in its infinite wisdom had been sited right next to a dual carriageway. For that reason, there was always a chance that a car might be nearing, but because of something to do with angles, which his maths teacher had once explained in class, it was impossible to see until the car had turned the corner, and by then, of course, it would be too late. That’s why the dare involved rolling all the way to the end, as far as the corner. With no chickening out en route as that would otherwise count as a forfeit.

He’d already decided during lunchtime that he was going to go first.

No point in prolonging the agony – the more time he had to think about it, the less chance of him actually going through with it, and then there’d be hell to pay. So almost before anyone had had a chance to undermine his confidence, he was already hurtling to the finish line, eyes tightly shut, intoning something between a hum, a moan, and an om.

It was the best feeling as he walked back up the ramp. Even better than the one he got most lunchtimes when pushing his arms out really hard to the side against the indented gate posts on one side of the playground. If he did it long enough, to the point where he thought he was going to pass out, and all the blood had rushed to his head, then when he staggered away his arms would briefly remain locked in the adjacent position, as though he was levitating with little Local Authority wings.

But this was far more powerful. His body felt lighter now than it had done for some time, and even the air suddenly tasted good.

The school seemed deserted, though he knew the caretaker would be doing his rounds. His other main fear had been if Mr Dhaliwal, his maths teacher, had caught them during the dare. Not because he was a big man who seemed to be the one teacher the kids were wary of, but because he wore a turban. Without even needing it explained to him, he knew that these few yards of starched cloth somehow meant that they – he and the teacher - were connected; that his actions would bring shame upon more than just himself, and that word would rapidly get back to mum, meaning, once again, there’d be hell to pay.

As for his adversary, even under the blond crop, and the normally dull eyes, something else was flickering, and when the guide looked more closely, he recognised the falter between fear and indecision.

The effects of the lunchtime swag – tizer, crisps and chocolate – which the group had lifted from the local shop as an à la carte alternative to the canteen gruel, were starting to show. The mood, already restive, rapidly morphed into something harsher, a default cruelty which evidently came as easily to these kids as petty theft.

Paul Martin may have been top dog at lunchtime, but now he was just another whimpering mutt in the crosshairs. And seeing this, the guide held his tongue, knowing that all he needed to do was let nature run its course.

Once the initial encouragement of his fickle entourage had turned to goading about the size, and presence, of his insides, Paul Martin made as if to crouch down into the foetal position. By now, it was obvious to everyone that he was scared. There was little breeze on hand to disperse the smell of his accumulating fear. At which point something else was said about another part of his anatomy.

And then he was off, but unlike the guide, rolling very slowly. It was hard to say whether he heard the car or the shouting. But by that point it was too late.

Everyone else had scattered once they’d heard the booming sounds of Mr Dhaliwal’s voice. In the confusion, the guide managed to snuck behind a grass verge leading up to the ramp.

Also alerted by the sounds of shouting, the Ford Cortina had slammed on its brakes, only just managing to stop a couple of feet in front of the shivering ball. Its driver sat trembling, too, but otherwise still, hands gripping the steering wheel. And suddenly it was so quiet that the guide could even hear his own breaths quicken as they counted the scene change.

One, two, three, ‘You!’

Four, five, six, ‘Up!’

Seven, eight, nine, ten, eleven, ‘Now!’

Mr Dhaliwal was trying to help the ball-shape to its feet, though it was clear that there were other complications. The teacher had a handkerchief pressed to his nose as the shape painfully attempted to revert to its familiar, class bully form. But even from a distance, the guide could tell that something had changed; some small shift in the cosmic balance. For once, the class bully was moving very gingerly, as if each step was a counting marker of his growing shame.

And although this all happened so long ago that it could almost be another life, the guide still swears, on those rare occasions he steps out of the late afternoon shadows, that as the maths teacher and the class bully drew closer to the verge, even through the grass he could make out the grin on the big Sikh’s face.

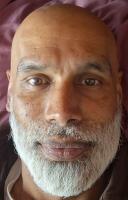

Koushik Banerjea is the author of two novels, both written while still the sole carer for his late mother: Another kind of Concrete (Jacaranda 2020) & Category Unknown (London Books 2022). His short stories have appeared in: FeignLit, Jerry Jazz Musician, Salvation in Stereo, Minor Literatures, Verbal, Writers Resist, and in the crime fiction anthologies, Shots in the Dark and Shots in the Dark II. He has had poems published in: Building Bridges, Third Space (Renard Press), Mogadored (Tangerine Press), Spinners, Scumbag Press, Razur Cuts magazine and online in House of Poetry magazine. A former youth worker and DJ, he has also previously worked as a journalist. Koushik recommends KhalsaAid.