Dr. Gonzo

Dr. Gonzo

A series of loosely related essays on equality, visibility, and modern mental health, or, How the Mental Health System Drove Me Crazy

by Dr. Deb Hoag

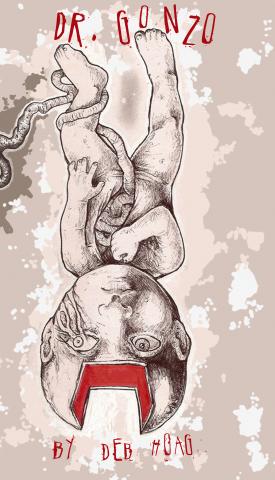

Dr. Gonzo: A series of loosely related essays on equality, visibility, and modern mental health, or, How the Mental Health System Drove Me Crazy details Dr. Hoag's efforts to provide effective psychotherapy in a nation of apathetic lawmakers and actively hostile insurance companies. Check out the cover art by Gabriel Vrooman, and the opening passage:

Tap, tap, tap with the pen, and waiting to hear footsteps down the hall. That last-minute check, do I need to pee? Can't leave once the client gets here, so peeing is important. Don't want to be stuck for an hour while the pressure builds up, like a panicked kid stuck on a church pew between a sanctimonious mother and stern father. Should I turn the thermostat up, down? Is that gas building in my stomach? Horrible, to be inside a small room and get gas, watching the client's face for signs he or she smells it, not acceptable to simply say "excuse me, mind if I fart?"

Tabula Rasa, blank slate. Freud wasn't the proponent of tabula rasa that people think he was. He saw patients in his home. He knew them socially. According to at least one patient, he knew them Biblically as well. He ate herring with them and shared his beloved schnapps, a little alcohol to lubricate the dream machine.

There are several different meanings to the phrase tabula rasa and the term is employed in a number of different fields; the meaning I refer to here is the one that is used to justify the cool distant cut-off between therapist and patient. A therapist who is a blank slate to the client thereby becomes a screen on which the patient's beliefs about self and others are projected, allowing the therapist greater insight into the inner mechanisms of the patient's psyche. This works great with patients who have a borderline personality disorder (BPD), by the way. In fact, it works so great that you don't really need to maintain a blank slate at all, because: A) patients with Borderline Personality Disorder find out everything about you anyway, and B) even when someone with BPD knows everything there is to know about you, they project like hell regardless.

The client's getting closer as I flip through my available game-faces, so to speak. Matron, patron, therapist, geek. Advisor, counselor, fix-it chick, chief.

So many things to think of, so many things to do before the client comes stepping softly down the hall, stomping down, sashaying down. Where the hell is the schnapps when I need some?

More tapping as I wait, and then he comes, secret center of my world for a little while, for a short while, for that brief slice of my life, a single hour, like a drop of crystal that shimmers and drops from the branch. The most precious thing I have in life is my time. It's all mine, and all I really have to give. What's money except the physical manifestation of time I have given away? Isn't that the crux of slavery, of school, of taxes—having our time forcibly taken from us?

Tap, tap, tap and I wait, as preoccupied with my bodily fluids and gasses and processes as any anal-retentive, excrescence-obsessed, certifiable lunatic. Flatulence, let me have none, I pray to the God of Disgusting Body Functions. With each client I accept, I am forced further and further into a childlike state of my own making, the lofty doctor who plays in the mud. I went to school with people who were in love with the idea of being a doctor and all that the position implied—nobility, wisdom, culture, wealth. Now they spend eight hours a day—eight forty-five minute hours a day—with people they never would have willingly let take out their trash in any other circumstance. Does the irony strike them? Do they become humble, more kindly, more Christlike in their practice? Or do they bury the dichotomy in dreams of social climbing and pretend it doesn't exist?

My fingers drum madly as I contemplate the frozen faces of colleagues past, nostrils pinched in distaste at the undergrad students rushing through the hallways. Do they sit and mimic compassion now as a stinking bundle of insanity sits on their tasteful furniture and talks shit? Talks shit about shit, while they try not to hear and pretend to listen. I had a co-worker who kept a couch cover especially for schizophrenic company, slipping it clean over her furniture before the most offensive clients came in, and then peeling it off immediately following the session to be washed, so that no putrid, crazy ass-cheeks could contaminate her lovely wing-back sofa.

There is a timid sound at my door, knuckles brushing softly on the wood, and I call 'come in.' The door opens slowly—just a few inches—enough to admit the face of this morning's patient. His eyes are serious, frightened that the Holy Roman Doctor is going to find fault, is going to reject, humiliate, crush him for his failures. He's been to counselors before, plenty. But the PhD throws him.

I stop tapping. I smile. I say, "come in and make yourself comfortable. I need to step out for just a minute."

He shuffles in, cautious, in case this is a trick, and gingerly sits on the edge of the chair facing mine. I stand and smooth my trousers, then make for the door. I have to piss like a racehorse, and I sprint down the hallway for the john.

Behind me, I can feel the questions rising up like proverbial crows, flapping around the client's head. "Is it me? Is it me? Is it me?"

Dr. Gonzo: A series of loosely related essays on equality, visibility, and modern mental health, or, How the Mental Health System Drove Me Crazy is out of print, but is still available as a free e-book from Smashwords.