Buy the paperback at Barnes & Noble or the ebook on Amazon!

Aileen Bassis showed me the first edition of “The Other Side of the Mirror” during a shared residency at an Arkansas writers’ retreat in late 2023, far from our homes in New York City. I was terribly impressed and moved. I felt Aileen had captured something essential about the long shadow of history and the pernicious legacy of slavery on all Americans.

Re-reading a new edition of the chapbook you now hold in your hands, I am even more struck by the singular power of Aileen’s vision – not to mention the haunted but restrained language she uses to construct her considerable and impressive poetic project.

Aileen has done this with admirable agility and fleetness: 17 poems in 21 pages, with not a word wasted anywhere. Each poem conveys the gravity, weight and damning power of historical significance and consequence. And each thrums with life and quiet, understated vitality.

First, about the poet’s vision. Aileen’s is history made manifest. Through the smart and careful use of citations from “The Secret Diary of William Byrd II,” the poet has opened up a whole world to contemporary readers.

This is the world of Black humans as chattel, their humanity denied and exploited by the likes of Byrd, an 18th century figure perhaps best known as the founder of Richmond, Virginia (later to become the capital of the Confederate States of America) and an enslaver and tobacco plantation owner.

It is Byrd’s role as slave owner that grounds this impressive collection. From the very first poem, “Plantation in 1709,” we sense the extremes of power imbalances. Byrd enjoys a life of ease and comfort – eating well (enjoying “battered eggs and pork,/ beef hash and buttered bread”) and drinking well (imbibing French wine and apple cider).

His life is contrasted with the experiences of an unnamed Black slave woman. She “ran away three times” and when “night fell,” was able to escape, having previously run away “with a metal bit / fixed between her lips” and punished by being confined in a shack, her hands and feet bound and tied.

The reader cheers the unnamed woman on. But there is also reason to pause, reflect, and maybe even shudder: did she make it to freedom in Canada? Or did she lose “her way / in the woods along the river?”

We don’t know, as there is no telling “how the story ends.”

Here we are struck by Aileen’s use of silence – silence that the poet respects, never daring to speak for the victim, but that keenly affirms the slave woman’s humanity and resilience. And yet it is also grim and damning: Master William, we are told, never even “wrote her name.” This is not a quiescent silence but silence tinged with sorrow, grief and even horrors.

It is also a reminder of the double-edged nature of power as understood in the Enlightenment times of Master William Byrd – the nascent sense of democratic political power to persuade and influence, and the power a colonial (soon to be American) slave-holding class had to dominate, exploit and brutalize an entire race of humans.

I have spoken of Aileen’s vision. Let me also praise her use of restrained but poignant language, with striking details that flesh out a narrative. These include “a rake lying in a field,” the aforementioned “metal bit fixed between her lips” and, perhaps most memorably, mud becoming a shroud during the woman’s escape, and the possibility that her ghost “wanders between cypress trees.” This is haunting, disturbing and visceral language, but beautifully crafted.

If these poems take on the troubling dynamics of race, class and gender, they do so in ways that never skirt complexity. We are told in the poem “May 22, 1709” that Byrd’s wife, Lucy, was responsible for the whipping of some of the slaves on her family’s planation. The poet addresses Lucy in the next poem, a prose reflection (“Letter from the 21st Century”) and acknowledges bafflement and anger. But she also expresses unsettling wisdom:

“I’m three hundred years away from you, and human cruelty continues,” Aileen writes. “Genocides continue, refugees are herded into camps, groups of people are demonized, enslavement continues in different forms and Black and brown bodies are at risk for violence every day.”

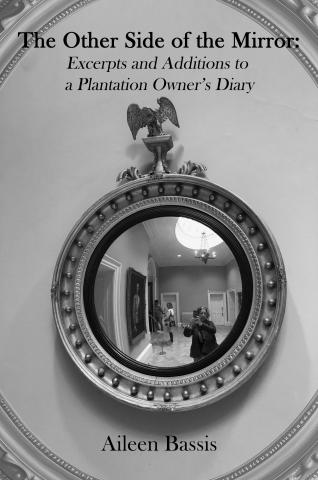

Not judging the past is impossible, the poet argues, but we are still left with “disillusion and perplexity” – the kind of ever-present realities that should give us all pause and make us look at the other side of the mirror in the present day, the present moment.

In a humane but pointed way, Aileen Bassis helps us confront the past and its continued contours and shadows over our lives as Americans in the still-unsettled 21st century – a moment in the history of a divided country when there is yet no telling “how the story ends.”

—Chris Herlinger, journalist, author, and poet

Check out what others are saying about The Other Side of the Mirror:

In The Other Side of the Mirror, Aileen Bassis uses her clear eyes, ears and verse to do what poetry does best; she can't find the names of some of the women and men here, but she can sing what happened to them back to us, sing it so it haunts your ears, ripples against our own tense days.”

—Cornelius Eady, Cave Canem founder, McClung Chair in English The University of Tenn-Knoxville

A plantaion owner’s secret diary revels in the casual cruelty and unbridled violence of slavery in Aileen Bassis’ chapbook The Other Side of the Mirror. After being beaten by tongs ‘she sprawled/unbundled like tobacco leaves...ready to be baled and sold’ in ‘Lucy Beats Her Girl.’ Brave urgent poems which should shame all who witness but do not speak.”

—Terese Svoboda, Guggenheim Fellow, award-winning author